By Samantha Tisdel Wright

Richard Ezra Fowler, aka “Mr. Dick,” was an iconic Ouray character, spanning the old and the new as effortlessly as he spun tales from his stool of honor at the Buen Tiempo. The former operator of Ouray’s historic hydro plant passed away last week. He was 67.

As this paper reaches readers’ hands, Fowler’s memorial service at the Ouray Ice Park will have taken place – it was set for Thursday evening. And surely many a margarita will have been lifted afterward in his honor at the Buen, where his barstool has been temporarily retired. And just as surely, many a “Mr. Dick” story will have been told.

How Fowler ended up in Ouray in the early 1990s is a story worth telling in itself, and is best done so by Fowler’s former employer and good friend Eric Jacobsen, owner of the Ouray Hydro Plant.

“Dick and I go back to the late ’80s when he had a Jeep repair garage in Grand Junction,” recalled Jacobsen, who also owns the famous Bridal Veil hydroelectric plant near Telluride, accessed via Imogene Pass. “We used old Jeeps for doing all the work (at the Bridal Veil plant),” Jacobsen said. “Dick had a little shop with a wood stove. We’d drag our Jeeps in, in the fall, and he’d spend the winter fixing them for us.”

At that time, Jacobsen was in the process of getting his bid together to buy the Ouray Hydro Plant from Colorado Ute, a regional utility which eventually went bankrupt. He got the plant for $10 because he was the only pre-qualified bidder. But that’s another story.

Over that winter, Fowler got word of Jacobsen’s new acquisition. “He showed up with his toolbox in hand and said he’d decided he wanted to be a hydro plant operator,” Jacobsen laughed. “He said he’d sure be glad if I hired him, but if I didn’t, he’d work for free.”

Fowler was hired, and moved right in. “He’s basically lived there ever since and has been very intimately involved in every aspect of the operation,” Jacobsen said.

Fowler came by his technical know-how by way of two hitches served in the U.S. Army, starting when he was only 18. He was stationed on the border of East and West Germany, where during formative years, he was in charge of a big truck maintenance garage.

The experience shaped the way he saw the world and lived his life. “He always had a very military viewpoint toward his work at the hydro plant,” Jacobsen said. “His idea was to keep the lieutenant happy but kick him out the door as soon as you can. I was always the lieutenant … Dick was the master surgeon.”

Fowler applied his military mentality to his hydro plant employees, too, including his right hand man, and in Jacobsen’s words “heavy lifter” of many years, Jimmy Pew. “Jimmy, unfortunately, was the private,” Jacobsen joked. “Either they loved Dick or they hated Dick, but he used his military structure on those guys; that’s how Dick ran the power plant.”

Jacobsen was happy to leave the running of the plant largely in Fowler’s hands, and like a good lieutenant, gave him plenty of space to do just that. ”I literally had not been in his apartment since he moved up there in 1992,” he said. “That was Dick’s world.”

Fowler retired from his position at the hydro plant about 18 months ago. New operator Chris Babbins now keeps things the old thing spinning. But it wasn’t long after Fowler stepped down from his operator position that he found his way back, this time as caretaker, doing maintenance work on an hourly basis.

“I think Dick frankly got tired of being retired,” Jacobsen chuckled.

Fowler’s boots at the plant will be hard to fill. “He was totally into old equipment,“ Jacobsen said. “He had the perfect personality to keep the hydro plant running. Dick would complain loudly when we had occasion to upgrade old equipment. He liked mechanical things and was very suspicious of anything electronic.”

Now, as for Fowler’s famous story-telling ability… “He had all sorts of funny stories,” Jacobsen said. “He had a way of making anything sound funny. It’s hard to do that.”

But interestingly, Fowler talked very rarely about his family.

“Funny stories and mishaps with machinery were more Dick’s thing,” Jacobsen said. “He was a good storyteller, so you didn’t mind if he’d recycle a story every few months. There’s all sorts of funny stories Dick had about daily life, and he never was the hero in any of them. His stories were always very complimentary of some other person for having patience and humility; listening to him was kind of like having zen lessons. He was very self-effacing. He just loved Ouray and the people here.”

And not surprisingly, Fowler had a knack for tapping into what makes the town tick. In addition to his work at the hydro plant and his estimable position at the Buen Tiempo, he was also a “de facto” member of the Ouray Mountain Rescue Team. To this group, Fowler’s snow-cat maintaining skills proved invaluable.

“He hung out with the young rock climber group and took the Ice Park very seriously,” Jacobsen said, adding that Fowler helped build the very first catwalk at the Ice Park in the early 1990s. “He had really, really good friends in Ouray – young, old and everywhere in between. He was a very happy, warm Ouray character.”

Fowler was born on a farm in Salida, the town where his mother and sister still live. He is also survived by a brother in Loveland, and his companion of many years, Mary White, who resides in Fruita. (White has bequeathed Fowler’s beloved old Jeep to Jacobsen.)

Prior to his stint as a mechanic in Grand Junction and his long-term gig in Ouray, Jacobsen said that Fowler worked in construction and as a truck driver.

“I think he always wandered a little bit until he found his way to Ouray,” Jacobson speculated. “Once he found the hydro plant, I think that that’s what he considered he wanted to do for the rest of his life.”

Monday, September 28, 2009

Friday, September 18, 2009

Ouray Bypass Construction

OURAY — Ouray County is seeking nearly $16 million in federal stimulus funds to reconstruct and pave County Road 1 over Log Hill Mesa and connecting roads to Highway 62 west of Ridgway.

The Board of County Commis-sioners on Monday approved the final version of a Tiger Grant application, made available through the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act, following its review during a special meeting on Sept. 8. The grant application was due Sept. 15.

The proposed 15-mile project would upgrade County Roads 1 from Colona over Log Hill Mesa and CR24 and CR 24-D through the east end of Pleasant Valley. County commissioners conceded after last week’s review that the project could make the route a bypass of Ridgway by funneling traffic off Highways 550 and 62.

“This will be a more efficient bypass road," said Commissioner Keith Meinert last week. But, Meinert noted, issues of speed limits, signage, weight limits and traffic enforcement need to be addressed. “I may lean toward favoring it when these questions are answered. People will need to know what the implications are.”

BOCC Chairman Heidi Albritton said last week that the BOCC will fully field public comment to see if county residents “have the political will” for the project, should funding be obtained.

On Monday, Albritton complimented county staff, in particular Administrator Connie Hunt, for putting the grant application together so quickly and so professionally. Albritton said she knows the project may stir controversy.

“But I feel as elected officials it’s important for us to examine all options that will help the community,” said Albritton.

Meinert echoed Albritton’s comments. “I want to assure the public that it can air any concerns,” said Meinert. “We will hold a public forum … if we get this grant. We are not making a commitment today.”

The grant application cites a potential benefit of creating a more convenient and shorter route (by nearly four miles) than the 19-plus miles on the Highway 550 and Highway 62 corridor through Ouray County.

Other benefits include improving safety for school buses and emergency response vehicles, winter travel and by reducing the number of vehicles that use Highway 62 through Ridgway for commuter or delivery travel between Montrose and Telluride; reducing dependence on oil and gas by providing an alternate route that is about 20% shorter; and enhancing air quality by reducing vehicle emissions and particulate matter from (gravel road) dust and the road-surface placement of sand during winter.

“It was a huge project pulling this together,” said Albritton. “It (the application packet) is really well thought out and pulls the picture together. We have a lot of good information to share at a public forum.”

A complete digital copy of the grant application is available at the Ouray County website: www.ouraycountyco.gov/

— By Patrick Davarn, news editor

The Board of County Commis-sioners on Monday approved the final version of a Tiger Grant application, made available through the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act, following its review during a special meeting on Sept. 8. The grant application was due Sept. 15.

The proposed 15-mile project would upgrade County Roads 1 from Colona over Log Hill Mesa and CR24 and CR 24-D through the east end of Pleasant Valley. County commissioners conceded after last week’s review that the project could make the route a bypass of Ridgway by funneling traffic off Highways 550 and 62.

“This will be a more efficient bypass road," said Commissioner Keith Meinert last week. But, Meinert noted, issues of speed limits, signage, weight limits and traffic enforcement need to be addressed. “I may lean toward favoring it when these questions are answered. People will need to know what the implications are.”

BOCC Chairman Heidi Albritton said last week that the BOCC will fully field public comment to see if county residents “have the political will” for the project, should funding be obtained.

On Monday, Albritton complimented county staff, in particular Administrator Connie Hunt, for putting the grant application together so quickly and so professionally. Albritton said she knows the project may stir controversy.

“But I feel as elected officials it’s important for us to examine all options that will help the community,” said Albritton.

Meinert echoed Albritton’s comments. “I want to assure the public that it can air any concerns,” said Meinert. “We will hold a public forum … if we get this grant. We are not making a commitment today.”

The grant application cites a potential benefit of creating a more convenient and shorter route (by nearly four miles) than the 19-plus miles on the Highway 550 and Highway 62 corridor through Ouray County.

Other benefits include improving safety for school buses and emergency response vehicles, winter travel and by reducing the number of vehicles that use Highway 62 through Ridgway for commuter or delivery travel between Montrose and Telluride; reducing dependence on oil and gas by providing an alternate route that is about 20% shorter; and enhancing air quality by reducing vehicle emissions and particulate matter from (gravel road) dust and the road-surface placement of sand during winter.

“It was a huge project pulling this together,” said Albritton. “It (the application packet) is really well thought out and pulls the picture together. We have a lot of good information to share at a public forum.”

A complete digital copy of the grant application is available at the Ouray County website: www.ouraycountyco.gov/

— By Patrick Davarn, news editor

Saturday, September 12, 2009

Ouray Real Estate and Water

Written by: Allan Best - Ouray County Watch

Posted by: Erin Eddy

www.ridgwayland.com

www.ourayland.com

With demographers forecasting 35 percent more people in Colorado by 2035 and climate scientists predicting 15 percent less water available in the Colorado River Basin by mid-century, something has to give.

More and more, public officials, business groups and environmental organizations have been talking about additional dams and reservoirs to augment those built in the mid-20th century.

“The water inheritance is running out,” said Josh Penry, the minority leader in the Colorado Senate, in a speech at the summer meeting of the Colorado Water Congress, a consortium of water providers. “Colorado needs to embark on a new round” of storage construction.

“We study too much. We analyze too much,” added Penry, who is from Grand Junction and a candidate for the Republican nomination for governor.

Representatives of environmental groups concede the need for additional storage but also call for restraint.

“There are projects that have significant adverse environmental impact that we could not support,” said Melinda Kassen, managing director of the Western Water Project for Trout Unlimited. “And there are projects that have substantially fewer environmental impacts that we can support,” she said, if mitigation measures are included.

Hovering over these conversations is the ghost of Wayne Aspinall. A onetime schoolteacher and lawyer from the fruit orchards of Palisade, Aspinall possessed neither good looks nor a good speaking voice. He did have a solid command of legislative techniques, however, and an ardent belief in the need to harness and regulate the rivers of the Rockies.

Serving in the U.S. House of Representatives from 1949 to 1973, Aspinall helped obtain authorization and federal funding for a series of major dams in the upper Colorado River Basin. Utah’s Lake Powell was the most massive, but a trio of reservoirs on the Gunnison River also resulted from his legislative perseverance. Today, they are collectively designed as the Aspinall Unit.

Growing populations

But if Westerners saw the yoking of rivers into submission as the major task of the mid-20th century, today a more nuanced challenge exists. The limits of abundance have become more apparent.

Most, if not all, of the best dam sites have been taken. Few reliable water supplies remain unclaimed, and those that are unclaimed, such as on the Yampa River of northwestern Colorado, are far from population centers.

Coloradans in the future, as is already the case, can be expected to congregate along the urbanized Front Range corridor. More than three-quarters of the state’s residents currently live in a narrow swath less than 200 miles long. The State Demography Office projects that the population, now at 5 million, by 2035 will nudge 7.8 million – an increase roughly the existing size of metropolitan Denver-Boulder.

Even more staggering population growth has been projected by 2035 for what is called the Colorado River system, an area that includes Denver, Salt Lake City and Los Angeles. The existing population of 24 to 30 million people will have grown by another 12 to 15 million. Imagine Las Vegas 11 times over.

In contrast to this uphill population climb, climate scientists see a downward slope for water. Temperature is the major driver.

Computerized simulations differ substantially as to whether precipitation will increase or decrease. Further, existing precipitation patterns could change, as increased planetary heat alters flow of the jet stream. In other words, changes in Vail and Telluride might not be uniform.

There’s more certainty about increased heat. Rising temperatures will produce shorter winters, more evaporation and transpiration, and a substantial reduction of total flows in the Colorado River. Scientists in the last two years have settled on a 15 percent reduction as a central figure.

“We are expecting a 39 percent increase in population and, if you want an average, a 15 percent reduction in supplies,” said Taylor Hawes, of The Nature Conservancy, describing the seven-state Colorado River Basin.

“By most standards, that’s a crisis.”

Managing uncertainty

Further confusing water planning is the prospect of drought. Colorado had several significant droughts in the 20th century, but all are overshadowed the mega-droughts of the distant past. Study of tree rings across the Southwest conducted by Connie Woodhouse of Arizona State University and other dendrochronologists shows clear evidence of extended drought periods, from roughly 1,000 years ago, that lasted up to three decades.

The parched summer of 2002, a time of roaring wildfires near Denver, Durango and Glenwood Springs, caught water managers by surprise. Levels in Lake Powell dropped precipitously in 2003, and by late 2004 had left bathtub rings two-thirds below the high-water mark. Many wondered if the reservoir might actually drop to a dead pool, unable to generate any electricity.

Along Colorado’s Front Range, the situation looked equally bleak. Had it not been for a miraculously wet and heavy snowstorm in March 2003, cities and farmers might have faced another withering summer, hot and dry.

Water managers broadly embrace the theory of human-caused global warming. Their meetings for the last several years have focused on the sharp warnings coming from climate scientists.

“The science is all basically painting in the same direction,” says Eric Kuhn, general manager of the Colorado River Water Conservation District.

But if the all signs point toward hotter and drier, great uncertainty remains. Faced with that uncertain hydrological future, Marc Waage, manager of water resources planning for Denver Water, says he has been “scratching my head for the last two years” about how to create a long-range water plan.

Before, water planning was a lot easier. There was always population growth, of course, but planners assumed a worst-case scenario that resembled a previous drought. Colorado’s documented worst drought came in the mid-1950s – about the time that Wayne Aspinall was proposing to dam the Gunnison, San Juan, and Green rivers.

Now, water planners realize much more serious droughts are possible and that even the average amounts of water will be less. Runoff will occur weeks and perhaps months earlier, leading to much longer, hotter and drier summers. Combined with population growth, all this suggests that the existing water infrastructure may be inadequate.

The elephant of Colorado

Colorado’s big question mark remains the urban Front Range corridor, especially Denver’s southern suburbs that overwhelmingly rely upon underground water that has become steadily more difficult to extract.

Prairie Waters Project, a major new diversion project to be completed in 2011, will draw water from the South Platte near Brighton several dozen miles south for use in Aurora, located on the eastern flanks of Denver. Short as the pipeline is, this project is expected to cost nearly $700 million.

Far more ambitious projects have been conceived. The most spectacular, proposed by former Montrose farmer Aaron Million, would draw water from the Green River near Rock Springs, Wyo., piping it along Interstate 80 and then down to the Front Range.

More recently, a rival plan employing the same idea has begun to emerge from a consortium of water providers in Denver’s southern suburbs.

Another so-called big straw would draw water from the Yampa River west of Craig. That idea comes from the Northern Colorado Water Conservancy District, the agency responsible for the Colorado Big Thompson project. The project, which takes water from Grand Lake to Estes Park, was described by Telluride native and historian David Lavender as a “massive violation of geography.”

These big straws have mostly been painted as saviors of agriculture. The thinking is that without further Western Slope diversions, the cities will end up buying farms for water.

But does the water exist?

Whether Colorado actually has sufficient water under the treaty apportioning the Colorado River Compact is open for debate. Kuhn, for example, has long suggested that Colorado has no more than a few hundred-thousand acre-feet of unallocated water. A study to be completed later this year by the Colorado River Water Board will, it is hoped, answer with greater certainty just how close Colorado is to the last drop.

Another set of studies will attempt to push the science of climate change even more rigorously. Tapping the expertise of scientists assembled in the federal laboratories at Boulder, these studies, it is hoped, will provide a better idea of how much water may exist in a hotter and drier future.

The focus naturally is on the Western Slope, where three-quarters of Colorado’s water originates, mostly in the form of snow. The studies will also attempt to predict how much precipitation regimes will change between basins – the San Juan, for example, as distinct from the Eagle.

While this gets sorted out, parallel roundtable discussions have been occurring regarding the state’s major river basins. The intent of these roundtables is to reach some larger consensus about water allocations, perhaps similar to the compacts that govern the Colorado River now.

Friction

If the roundtables have improved dialogue, tempers have occasionally flared. Disagreement was evident in one exchange at last month’s meeting of the Colorado Water Congress. Pitkin County Commissioner Rachael Richards complained that Western Slope water had not been given its due in generating revenue in Colorado’s second largest economic, tourism and recreation.

She got pushback from Rodney Kuharich, director South Metro Water Supply Authority. Aspen, he observed, seemed to have done quite well despite the diversion of waters from the Roaring Fork River and its tributaries that began decades ago. Resorts on the Western Slope, he said, have benefited handsomely from customers drawn from along the Front Range.

As for additional storage, future reservoirs will likely be smaller but perhaps at higher-elevation locations, to minimize evaporation. But whereas the reservoirs of Aspinall’s day were all about commerce, today they will be judged against a greater matrix of considerations.

The Nature Conservancy’s Hawes said her group believes that decisions about storage should be guided by multiple uses, “so that the environmental is part of the planning and not an afterthought.”

Posted by: Erin Eddy

www.ridgwayland.com

www.ourayland.com

With demographers forecasting 35 percent more people in Colorado by 2035 and climate scientists predicting 15 percent less water available in the Colorado River Basin by mid-century, something has to give.

More and more, public officials, business groups and environmental organizations have been talking about additional dams and reservoirs to augment those built in the mid-20th century.

“The water inheritance is running out,” said Josh Penry, the minority leader in the Colorado Senate, in a speech at the summer meeting of the Colorado Water Congress, a consortium of water providers. “Colorado needs to embark on a new round” of storage construction.

“We study too much. We analyze too much,” added Penry, who is from Grand Junction and a candidate for the Republican nomination for governor.

Representatives of environmental groups concede the need for additional storage but also call for restraint.

“There are projects that have significant adverse environmental impact that we could not support,” said Melinda Kassen, managing director of the Western Water Project for Trout Unlimited. “And there are projects that have substantially fewer environmental impacts that we can support,” she said, if mitigation measures are included.

Hovering over these conversations is the ghost of Wayne Aspinall. A onetime schoolteacher and lawyer from the fruit orchards of Palisade, Aspinall possessed neither good looks nor a good speaking voice. He did have a solid command of legislative techniques, however, and an ardent belief in the need to harness and regulate the rivers of the Rockies.

Serving in the U.S. House of Representatives from 1949 to 1973, Aspinall helped obtain authorization and federal funding for a series of major dams in the upper Colorado River Basin. Utah’s Lake Powell was the most massive, but a trio of reservoirs on the Gunnison River also resulted from his legislative perseverance. Today, they are collectively designed as the Aspinall Unit.

Growing populations

But if Westerners saw the yoking of rivers into submission as the major task of the mid-20th century, today a more nuanced challenge exists. The limits of abundance have become more apparent.

Most, if not all, of the best dam sites have been taken. Few reliable water supplies remain unclaimed, and those that are unclaimed, such as on the Yampa River of northwestern Colorado, are far from population centers.

Coloradans in the future, as is already the case, can be expected to congregate along the urbanized Front Range corridor. More than three-quarters of the state’s residents currently live in a narrow swath less than 200 miles long. The State Demography Office projects that the population, now at 5 million, by 2035 will nudge 7.8 million – an increase roughly the existing size of metropolitan Denver-Boulder.

Even more staggering population growth has been projected by 2035 for what is called the Colorado River system, an area that includes Denver, Salt Lake City and Los Angeles. The existing population of 24 to 30 million people will have grown by another 12 to 15 million. Imagine Las Vegas 11 times over.

In contrast to this uphill population climb, climate scientists see a downward slope for water. Temperature is the major driver.

Computerized simulations differ substantially as to whether precipitation will increase or decrease. Further, existing precipitation patterns could change, as increased planetary heat alters flow of the jet stream. In other words, changes in Vail and Telluride might not be uniform.

There’s more certainty about increased heat. Rising temperatures will produce shorter winters, more evaporation and transpiration, and a substantial reduction of total flows in the Colorado River. Scientists in the last two years have settled on a 15 percent reduction as a central figure.

“We are expecting a 39 percent increase in population and, if you want an average, a 15 percent reduction in supplies,” said Taylor Hawes, of The Nature Conservancy, describing the seven-state Colorado River Basin.

“By most standards, that’s a crisis.”

Managing uncertainty

Further confusing water planning is the prospect of drought. Colorado had several significant droughts in the 20th century, but all are overshadowed the mega-droughts of the distant past. Study of tree rings across the Southwest conducted by Connie Woodhouse of Arizona State University and other dendrochronologists shows clear evidence of extended drought periods, from roughly 1,000 years ago, that lasted up to three decades.

The parched summer of 2002, a time of roaring wildfires near Denver, Durango and Glenwood Springs, caught water managers by surprise. Levels in Lake Powell dropped precipitously in 2003, and by late 2004 had left bathtub rings two-thirds below the high-water mark. Many wondered if the reservoir might actually drop to a dead pool, unable to generate any electricity.

Along Colorado’s Front Range, the situation looked equally bleak. Had it not been for a miraculously wet and heavy snowstorm in March 2003, cities and farmers might have faced another withering summer, hot and dry.

Water managers broadly embrace the theory of human-caused global warming. Their meetings for the last several years have focused on the sharp warnings coming from climate scientists.

“The science is all basically painting in the same direction,” says Eric Kuhn, general manager of the Colorado River Water Conservation District.

But if the all signs point toward hotter and drier, great uncertainty remains. Faced with that uncertain hydrological future, Marc Waage, manager of water resources planning for Denver Water, says he has been “scratching my head for the last two years” about how to create a long-range water plan.

Before, water planning was a lot easier. There was always population growth, of course, but planners assumed a worst-case scenario that resembled a previous drought. Colorado’s documented worst drought came in the mid-1950s – about the time that Wayne Aspinall was proposing to dam the Gunnison, San Juan, and Green rivers.

Now, water planners realize much more serious droughts are possible and that even the average amounts of water will be less. Runoff will occur weeks and perhaps months earlier, leading to much longer, hotter and drier summers. Combined with population growth, all this suggests that the existing water infrastructure may be inadequate.

The elephant of Colorado

Colorado’s big question mark remains the urban Front Range corridor, especially Denver’s southern suburbs that overwhelmingly rely upon underground water that has become steadily more difficult to extract.

Prairie Waters Project, a major new diversion project to be completed in 2011, will draw water from the South Platte near Brighton several dozen miles south for use in Aurora, located on the eastern flanks of Denver. Short as the pipeline is, this project is expected to cost nearly $700 million.

Far more ambitious projects have been conceived. The most spectacular, proposed by former Montrose farmer Aaron Million, would draw water from the Green River near Rock Springs, Wyo., piping it along Interstate 80 and then down to the Front Range.

More recently, a rival plan employing the same idea has begun to emerge from a consortium of water providers in Denver’s southern suburbs.

Another so-called big straw would draw water from the Yampa River west of Craig. That idea comes from the Northern Colorado Water Conservancy District, the agency responsible for the Colorado Big Thompson project. The project, which takes water from Grand Lake to Estes Park, was described by Telluride native and historian David Lavender as a “massive violation of geography.”

These big straws have mostly been painted as saviors of agriculture. The thinking is that without further Western Slope diversions, the cities will end up buying farms for water.

But does the water exist?

Whether Colorado actually has sufficient water under the treaty apportioning the Colorado River Compact is open for debate. Kuhn, for example, has long suggested that Colorado has no more than a few hundred-thousand acre-feet of unallocated water. A study to be completed later this year by the Colorado River Water Board will, it is hoped, answer with greater certainty just how close Colorado is to the last drop.

Another set of studies will attempt to push the science of climate change even more rigorously. Tapping the expertise of scientists assembled in the federal laboratories at Boulder, these studies, it is hoped, will provide a better idea of how much water may exist in a hotter and drier future.

The focus naturally is on the Western Slope, where three-quarters of Colorado’s water originates, mostly in the form of snow. The studies will also attempt to predict how much precipitation regimes will change between basins – the San Juan, for example, as distinct from the Eagle.

While this gets sorted out, parallel roundtable discussions have been occurring regarding the state’s major river basins. The intent of these roundtables is to reach some larger consensus about water allocations, perhaps similar to the compacts that govern the Colorado River now.

Friction

If the roundtables have improved dialogue, tempers have occasionally flared. Disagreement was evident in one exchange at last month’s meeting of the Colorado Water Congress. Pitkin County Commissioner Rachael Richards complained that Western Slope water had not been given its due in generating revenue in Colorado’s second largest economic, tourism and recreation.

She got pushback from Rodney Kuharich, director South Metro Water Supply Authority. Aspen, he observed, seemed to have done quite well despite the diversion of waters from the Roaring Fork River and its tributaries that began decades ago. Resorts on the Western Slope, he said, have benefited handsomely from customers drawn from along the Front Range.

As for additional storage, future reservoirs will likely be smaller but perhaps at higher-elevation locations, to minimize evaporation. But whereas the reservoirs of Aspinall’s day were all about commerce, today they will be judged against a greater matrix of considerations.

The Nature Conservancy’s Hawes said her group believes that decisions about storage should be guided by multiple uses, “so that the environmental is part of the planning and not an afterthought.”

Saturday, September 5, 2009

Ouray Historic Homes and Real Estate

Written by the Ouray County Watch

Sep 03, 2009 | 90 views | 0 | 1 | |

The Tanner/Viets house, built in 1901 in the Dutch Colonial Revival style, was owned by Frank and Ida Tanner. Frank was Mayor of Ouray from 1905-1907 and was director of the Bank of Ouray. This and other historic buildings are featured in the Ouray County Historical Museum’s newest exhibit: “Ouray’s Historic Homes,” on display now through Nov. 21 during regular museum hours. (Photo by Doris Gregory)

slideshow OURAY – The Ouray County Historical Museum’s newest exhibit originated as one of the OCHS Evening of History programs put together by Ouray resident Carolyne Kelly earlier this summer. Kelly’s program, “Ouray’s Historic Homes” received such an enthusiastic response that museum curator, Don Paulson, decided to wrap up the summer season with a special exhibit based on her presentation.

The exhibit features 12 homes built between 1877 and 1902 that represent several architectural styles: Pioneer Log, Folk Victorian, Late Victorian, Victorian/Italianate, Victorian/Queen Anne, Edwardian or Dutch Colonial.

“No one architectural style exists in Ouray,” explained Kelly. “Most of the homes in the Ouray National Historic District were built between 1876 and 1915, during the heyday of mining. These buildings are heavily influenced by architecture of the Victorian era which generally overlapped with Queen Victoria’s reign from 1837–1901.”

According to Kelly, the 12 homes selected for the focus of the exhibit were chosen for specific reasons: Kelly wanted to display a representative sampling of architectural styles, and some of the houses’ owners had interesting backgrounds and interconnected family histories.

The quality of available old photographs and the consideration of available exhibit space also dictated her selection.

The “Ouray’s Historic Homes” exhibit is located on the second floor of the Ouray County Historical Museum, which is housed in a beautiful 122-year-old stone building at the top of 6th Avenue in Ouray. The exhibit will run through Nov. 21. Museum hours are Monday through Saturday, 10 a.m.- 4:30 p.m. and Sunday, noon-4:30 p.m. Call the museum at 325-4576 for more information, or go online to ouraycountyhistoricalsociety.org.

Sep 03, 2009 | 90 views | 0 | 1 | |

The Tanner/Viets house, built in 1901 in the Dutch Colonial Revival style, was owned by Frank and Ida Tanner. Frank was Mayor of Ouray from 1905-1907 and was director of the Bank of Ouray. This and other historic buildings are featured in the Ouray County Historical Museum’s newest exhibit: “Ouray’s Historic Homes,” on display now through Nov. 21 during regular museum hours. (Photo by Doris Gregory)

slideshow OURAY – The Ouray County Historical Museum’s newest exhibit originated as one of the OCHS Evening of History programs put together by Ouray resident Carolyne Kelly earlier this summer. Kelly’s program, “Ouray’s Historic Homes” received such an enthusiastic response that museum curator, Don Paulson, decided to wrap up the summer season with a special exhibit based on her presentation.

The exhibit features 12 homes built between 1877 and 1902 that represent several architectural styles: Pioneer Log, Folk Victorian, Late Victorian, Victorian/Italianate, Victorian/Queen Anne, Edwardian or Dutch Colonial.

“No one architectural style exists in Ouray,” explained Kelly. “Most of the homes in the Ouray National Historic District were built between 1876 and 1915, during the heyday of mining. These buildings are heavily influenced by architecture of the Victorian era which generally overlapped with Queen Victoria’s reign from 1837–1901.”

According to Kelly, the 12 homes selected for the focus of the exhibit were chosen for specific reasons: Kelly wanted to display a representative sampling of architectural styles, and some of the houses’ owners had interesting backgrounds and interconnected family histories.

The quality of available old photographs and the consideration of available exhibit space also dictated her selection.

The “Ouray’s Historic Homes” exhibit is located on the second floor of the Ouray County Historical Museum, which is housed in a beautiful 122-year-old stone building at the top of 6th Avenue in Ouray. The exhibit will run through Nov. 21. Museum hours are Monday through Saturday, 10 a.m.- 4:30 p.m. and Sunday, noon-4:30 p.m. Call the museum at 325-4576 for more information, or go online to ouraycountyhistoricalsociety.org.

Saturday, August 22, 2009

New Ouray Real Estate Development

RiverSage the ‘Proper’ Way to Develop Land

by Gus JarvisAug 20, 2009

Posted by: Erin Eddy

www.ridgwayland.com

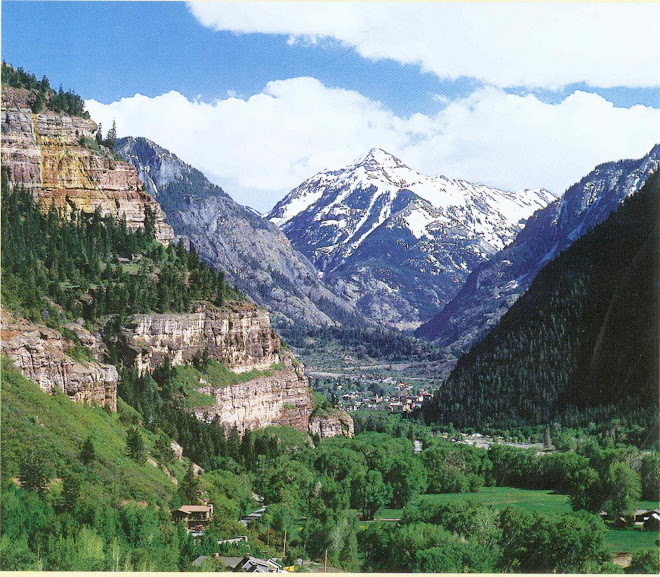

LAY OF THE LAND – Lot 3 in the first phase of the RiverSage sits next to cottonwoods that line the Uncompahgre River. It also has magnificent views of the Sneffels and Cimarron mountain ranges. (Photos by Gus Jarvis)

slideshow

slideshow Phase One Lots Now Available

RIDGWAY – Six years since the inception of the RiverSage subdivision, two miles north of Ridgway near the banks of the Uncompahgre River, seven two-acre home sites are now available for purchase. The sites represent the first phase of the development and provide future residents clear views of the Sneffels and Cimarron mountain ranges as well as access to over 100 acres of surrounding open space and the adjacent 60-acre Dennis Weaver Memorial Park.

The project’s developer Rick Weaver, who has been busy overseeing road paving at the subdivision, said that the process to create and annex the subdivision with the Town of Ridgway was a lengthy, but ultimately is a “win-win” development for potential lot owners as well as the those who will enjoy the 60-acre park. The development also encompasses the philosophy of Weaver’s late father, actor and environmentalist Dennis Weaver.

“We really wanted to preserve the river corridor, wetlands and wildlife habitat,” Weaver said in an interview last week. “We tried to keep his vision in approaching this project. The only way we could do this is donate land and develop just enough lots to make it financially feasible. The town got a 60-acre park and we got the lots we needed. Everybody wins with this project.”

Lots in the first phase of the subdivision are priced to sell from $289,000. With its location on the outskirts of Ridgway and within one hour’s drive of Telluride, the subdivision is perfect for those who want to be surrounded by San Juan Mountain beauty but not too far from the conveniences of town.

“What is really great about it is you get a rural country, private feel but you are only four minutes from town,” Weaver said. “You are also only four minutes from town if you want to ride your bike on the path. People can even go down to the [Ridgway] State Park without even getting into a car.”

The entire RiverSage subdivision is broken up into three phases and will, when it is complete, have just 20 lots on 115 acres of land.

“There is a lot of open space out there and a lot of great mountain views with no homes in front of another,” Weaver said.

In keeping with his father’s vision, Weaver said the subdivision will be environmentally sensitive and wildlife friendly. Guidelines in place ensure that each home is not only elegantly designed but energy efficient and economical.

“One of the things that we are excited to do is have a green development,” he said. “We have instituted voluntary green building codes that are based loosely on codes that are in effect in Telluride and in Gunnison. Most of it involves good building practices. We felt it is a worthwhile thing to do and we are proud of the fact we have taken those voluntary steps. I think it is absolutely necessary to worry about conservation.”

RiverSage is ideal for those who regularly get outside for recreation and exercise. For mountain bikers, the Eagle Hill loop is adjacent to the development, and for the angler, the fly-fishing on the nearby Uncompahgre River is “great,” according to Weaver.

“We have had a lot of compliments on the [Dennis Weaver Memorial] Park and its trail system,” he said. “This project is all about preserving the river corridor and open space while having a limited density and limited visual impact project that includes green building. It is something that is conscious of our environmental needs as well as conservation needs and we think it is the proper way to develop a piece of land.”

by Gus JarvisAug 20, 2009

Posted by: Erin Eddy

www.ridgwayland.com

LAY OF THE LAND – Lot 3 in the first phase of the RiverSage sits next to cottonwoods that line the Uncompahgre River. It also has magnificent views of the Sneffels and Cimarron mountain ranges. (Photos by Gus Jarvis)

slideshow

slideshow Phase One Lots Now Available

RIDGWAY – Six years since the inception of the RiverSage subdivision, two miles north of Ridgway near the banks of the Uncompahgre River, seven two-acre home sites are now available for purchase. The sites represent the first phase of the development and provide future residents clear views of the Sneffels and Cimarron mountain ranges as well as access to over 100 acres of surrounding open space and the adjacent 60-acre Dennis Weaver Memorial Park.

The project’s developer Rick Weaver, who has been busy overseeing road paving at the subdivision, said that the process to create and annex the subdivision with the Town of Ridgway was a lengthy, but ultimately is a “win-win” development for potential lot owners as well as the those who will enjoy the 60-acre park. The development also encompasses the philosophy of Weaver’s late father, actor and environmentalist Dennis Weaver.

“We really wanted to preserve the river corridor, wetlands and wildlife habitat,” Weaver said in an interview last week. “We tried to keep his vision in approaching this project. The only way we could do this is donate land and develop just enough lots to make it financially feasible. The town got a 60-acre park and we got the lots we needed. Everybody wins with this project.”

Lots in the first phase of the subdivision are priced to sell from $289,000. With its location on the outskirts of Ridgway and within one hour’s drive of Telluride, the subdivision is perfect for those who want to be surrounded by San Juan Mountain beauty but not too far from the conveniences of town.

“What is really great about it is you get a rural country, private feel but you are only four minutes from town,” Weaver said. “You are also only four minutes from town if you want to ride your bike on the path. People can even go down to the [Ridgway] State Park without even getting into a car.”

The entire RiverSage subdivision is broken up into three phases and will, when it is complete, have just 20 lots on 115 acres of land.

“There is a lot of open space out there and a lot of great mountain views with no homes in front of another,” Weaver said.

In keeping with his father’s vision, Weaver said the subdivision will be environmentally sensitive and wildlife friendly. Guidelines in place ensure that each home is not only elegantly designed but energy efficient and economical.

“One of the things that we are excited to do is have a green development,” he said. “We have instituted voluntary green building codes that are based loosely on codes that are in effect in Telluride and in Gunnison. Most of it involves good building practices. We felt it is a worthwhile thing to do and we are proud of the fact we have taken those voluntary steps. I think it is absolutely necessary to worry about conservation.”

RiverSage is ideal for those who regularly get outside for recreation and exercise. For mountain bikers, the Eagle Hill loop is adjacent to the development, and for the angler, the fly-fishing on the nearby Uncompahgre River is “great,” according to Weaver.

“We have had a lot of compliments on the [Dennis Weaver Memorial] Park and its trail system,” he said. “This project is all about preserving the river corridor and open space while having a limited density and limited visual impact project that includes green building. It is something that is conscious of our environmental needs as well as conservation needs and we think it is the proper way to develop a piece of land.”

Thursday, August 13, 2009

Ouray Real Estate Land Use Issues

Commissioners to Address Mining Claim Issues With Current Regulations

by Gus Jarvis Aug 13, 2009

Posted by Erin Eddy - www.ourayland.com and www.ridgwayland.com

OURAY – Instead of drafting an entire new section to the county’s Land Use Code to regulate residential development on patented mining claims, the Ouray Board of County Commissioners on Monday generally agreed that they would schedule series of work sessions that would be dedicated to specific concerns surrounding residential development on mining claims in hopes of better enforcing or tweaking existing codes.

Monday’s discussion was the first opportunity for the commissioners to formally discuss what they had heard at a July 27 forum held to discuss possible new regulations on the development of mining claims, attended by close to 200 county residents. It was apparent at the meeting that the community is sharply divided over the need for regulating residential development on mining claims.

While County Commissioner Keith Meinert said he thought that he and his fellow commissioners had clearly defined their concerns and objectives when they first started the process of drafting new regulations, he agreed that the commissioners should specifically outline why they are concerned about residential development on mining claims.

“I think the objectives and concerns still exist,” Meinert said. “I want to continue to pursue this to achieve clear cut objectives and address clear cut concerns and maybe we need to spend some time enumerating exactly what those concerns and objectives are.”

Meinert continued by saying that there is a possibility of addressing those concerns with existing site development permit regulations and visual impact regulations.

“The possibility of achieving those objectives and concerns by better enforcement and better tweaking of existing regulations is something we need to explore rather than the new section of code, which we had thrown out as a discussion vehicle for the planning commission.”

The commissioners set up a list of “bite sized” concerns that need to be addressed in future work sessions. First, they agreed to work with County Assessor Susie Mayfield to address the value that mining claims are assessed. Currently mining claims are generally valued by the assessor at $1,000 per acre, rather than the value assigned to other categories of vacant land in the county. “One issue that, to me, stood out is this taxation issue,” Commissioner Heidi Albritton said. “The valuation of mining clams is a touchy topic and a bit of a Pandora’s box. We need to have a discussion on how to deal with that.” Albritton added that she understood that it would be an expensive and lengthy process to reassess each mining claim.

Commissioner Lynn Padgett suggested that the first step the county could take is a mass appraisal system of mining clams and that the county look to the U.S. Forest Service as a partner in coming up with a means to survey the mining claims so the county can have “an accurate picture of where the parcels are.”

Albritton cautioned her fellow commissioners that if the valuations of those properties were to be changed, the board would first need to be completely educated on how the change would affect property owners.

“We also need to be cognizant of the impact to those people who have owned those properties and don’t plan to build on them,” Albritton said. “I don’t think we have a choice in the matter but there are going to be ramifications and it will affect people in a significant way. It could be the difference of people hanging on to [a mining claim] or putting it on the market.”

The commissioners also said they still had not heard concerns from residents about the visual impacts of unregulated residential development on mining claims and agreed that the current visual impact regulations need to be addresses so they can be better enforced and possibly broadened to more areas. Meinert said their were “obvious shortcomings” with the visual impact code and that it is currently “unworkable and is unenforceable.

“It allows a kind of discretion by staff that puts staff in a difficult position,” Meinert said. “I think we need to put a lot more thought into the visual impact code.”

Albritton agreed by suggesting that the commissioners schedule “a decent amount of time to workshop our visual impact regulations. We all know there are issues with that section of code and then also have simultaneous discussions about expanding the visual impact corridors.”

Continuing on, the commissioners agreed that road grade issue needs to be addressed as well. Meinert suggested that there be, in the LUC, a variance process to allow for road grades above 12 percent.

“I think there needs to be a variance process and it needs to recognize that some need to be more than 12 percent,” Meinert said. “The other issue is the need for a permitting process before any blade is put to the earth. That would potentially address some of the issues in getting the right kind of engineering.”

He added that the “biggest stumbling block” to development in mining claims areas is they are up private roads.

“Our regulations were intended in keeping those primitive,” he said. “I am not trying to resolve the issue here but it is another area to be addressed.”

Along with that, Meinert said the commissioners need to look into whether or not the county will require owners who develop off primitive roads to sign a waiver that would take away the county’s liability in providing emergency services.

“Something that clearly forces them to recognize that what they are doing in that location may have consequences to them,” Meinert said. Padgett added that she is concerned with what responsibility the county has in taking care of wildfires around those mining claims.

The commissioners directed County Attorney Mary Deganhart to draft a resolution that would specifically outline what the commissioners intend to work on in upcoming work sessions. It was unclear at Monday’s meeting what role the Ouray County Planning Commission would play in each of the work sessions, but the commission would be invited to all of them.

by Gus Jarvis Aug 13, 2009

Posted by Erin Eddy - www.ourayland.com and www.ridgwayland.com

OURAY – Instead of drafting an entire new section to the county’s Land Use Code to regulate residential development on patented mining claims, the Ouray Board of County Commissioners on Monday generally agreed that they would schedule series of work sessions that would be dedicated to specific concerns surrounding residential development on mining claims in hopes of better enforcing or tweaking existing codes.

Monday’s discussion was the first opportunity for the commissioners to formally discuss what they had heard at a July 27 forum held to discuss possible new regulations on the development of mining claims, attended by close to 200 county residents. It was apparent at the meeting that the community is sharply divided over the need for regulating residential development on mining claims.

While County Commissioner Keith Meinert said he thought that he and his fellow commissioners had clearly defined their concerns and objectives when they first started the process of drafting new regulations, he agreed that the commissioners should specifically outline why they are concerned about residential development on mining claims.

“I think the objectives and concerns still exist,” Meinert said. “I want to continue to pursue this to achieve clear cut objectives and address clear cut concerns and maybe we need to spend some time enumerating exactly what those concerns and objectives are.”

Meinert continued by saying that there is a possibility of addressing those concerns with existing site development permit regulations and visual impact regulations.

“The possibility of achieving those objectives and concerns by better enforcement and better tweaking of existing regulations is something we need to explore rather than the new section of code, which we had thrown out as a discussion vehicle for the planning commission.”

The commissioners set up a list of “bite sized” concerns that need to be addressed in future work sessions. First, they agreed to work with County Assessor Susie Mayfield to address the value that mining claims are assessed. Currently mining claims are generally valued by the assessor at $1,000 per acre, rather than the value assigned to other categories of vacant land in the county. “One issue that, to me, stood out is this taxation issue,” Commissioner Heidi Albritton said. “The valuation of mining clams is a touchy topic and a bit of a Pandora’s box. We need to have a discussion on how to deal with that.” Albritton added that she understood that it would be an expensive and lengthy process to reassess each mining claim.

Commissioner Lynn Padgett suggested that the first step the county could take is a mass appraisal system of mining clams and that the county look to the U.S. Forest Service as a partner in coming up with a means to survey the mining claims so the county can have “an accurate picture of where the parcels are.”

Albritton cautioned her fellow commissioners that if the valuations of those properties were to be changed, the board would first need to be completely educated on how the change would affect property owners.

“We also need to be cognizant of the impact to those people who have owned those properties and don’t plan to build on them,” Albritton said. “I don’t think we have a choice in the matter but there are going to be ramifications and it will affect people in a significant way. It could be the difference of people hanging on to [a mining claim] or putting it on the market.”

The commissioners also said they still had not heard concerns from residents about the visual impacts of unregulated residential development on mining claims and agreed that the current visual impact regulations need to be addresses so they can be better enforced and possibly broadened to more areas. Meinert said their were “obvious shortcomings” with the visual impact code and that it is currently “unworkable and is unenforceable.

“It allows a kind of discretion by staff that puts staff in a difficult position,” Meinert said. “I think we need to put a lot more thought into the visual impact code.”

Albritton agreed by suggesting that the commissioners schedule “a decent amount of time to workshop our visual impact regulations. We all know there are issues with that section of code and then also have simultaneous discussions about expanding the visual impact corridors.”

Continuing on, the commissioners agreed that road grade issue needs to be addressed as well. Meinert suggested that there be, in the LUC, a variance process to allow for road grades above 12 percent.

“I think there needs to be a variance process and it needs to recognize that some need to be more than 12 percent,” Meinert said. “The other issue is the need for a permitting process before any blade is put to the earth. That would potentially address some of the issues in getting the right kind of engineering.”

He added that the “biggest stumbling block” to development in mining claims areas is they are up private roads.

“Our regulations were intended in keeping those primitive,” he said. “I am not trying to resolve the issue here but it is another area to be addressed.”

Along with that, Meinert said the commissioners need to look into whether or not the county will require owners who develop off primitive roads to sign a waiver that would take away the county’s liability in providing emergency services.

“Something that clearly forces them to recognize that what they are doing in that location may have consequences to them,” Meinert said. Padgett added that she is concerned with what responsibility the county has in taking care of wildfires around those mining claims.

The commissioners directed County Attorney Mary Deganhart to draft a resolution that would specifically outline what the commissioners intend to work on in upcoming work sessions. It was unclear at Monday’s meeting what role the Ouray County Planning Commission would play in each of the work sessions, but the commission would be invited to all of them.

Saturday, August 8, 2009

Ouray Real Estate Land Use Issues

Split continues on mine claims regs

Written by: Patrick Davarn 07.AUG.09

Posted by: Erin Eddy - www.ourayland.com

Unscheduled discussion on the current hot-button topic of residential development on mining claims dominated an otherwise light agenda for the Board of County Commissioners.

Yet more discussion, albeit this time scheduled, takes place during a work session on Aug. 10 between the BOCC and the Ouray County Planning Commission (OCPC).

Last Monday, OCPC member Ken Lipton came before the BOCC during its informal Call to the Public to read a statement of timelines that included summaries of directives by the BOCC and meetings and work sessions since the process began in May 2008.

“The question as to whether or not a new section to the code should be written was already decided by the BOCC and earlier agreed to by the PC and this should not be negated by self-interested parties or ideology or fear of angering a portion of the community that holds unrealistic views on property rights or the county’s right to regulate land use,” said Lipton from a portion of his document.

According to a news report in the July 31 Plaindealer, nearly 200 citizens packed the county courthouse two days earlier to register their views on the issue of restrictions and regulations for residential development on mining claims. Opinions were as diverse as the backgrounds of those in attendance; some owned property in the area currently defined as the South Alpine Zone, some did not.

Commissioner Keith Meinert said at Monday’s meeting that a news report in last week’s Plaindealer needed clarification. County Attorney Mary Deganhart did not write or propose regulations for that zone. “We need to be careful in the way this is portrayed to the public,” said Meinert. “I want to dispel completely (any belief) that such work is driven by any individual on the staff. The county attorney is working at the instruction of the board.”

Meinert said he agreed with Lipton that there needs to be a better understanding between the BOCC and the Planning Commission.

BOCC Chairman Heidi Albritton said the county’s six-month moratorium on mining claims development was intended to allow time for discussion and consideration of specific regulations; but the timetable was not realistic. “We have a large demographic interested in the issue,” said Albritton. “If there are ways to work with them, we need to do that and get a consensus, understanding that we are not going to please everyone.”

Ridgway area resident Craig Fetterolf, who served on the county’s Study Group that earlier this year completed its report on two separate analysis on the affects of growth, asked why mining claims are not taxed the same as other buildable residential properties. “It’s unfair to the rest of us who are paying our taxes,” he said.

Meinert said mining claims are being assessed at the proper rate of 29%; there is no special treatment by the Assessor’s Office. Commissioner Lynn Padgett explained that the difference is the land’s valuation. Padgett said the state requires the county to assess all property at market value, but there is simply not enough data on local sales.

Padgett added that while a higher assessment of market value may add to property tax revenues, it may also harm opportunities for the public, such as the Red Mountain Project or the Trust for Public Land, to obtain mining claims. A higher valuation will mean a higher price.

Written by: Patrick Davarn 07.AUG.09

Posted by: Erin Eddy - www.ourayland.com

Unscheduled discussion on the current hot-button topic of residential development on mining claims dominated an otherwise light agenda for the Board of County Commissioners.

Yet more discussion, albeit this time scheduled, takes place during a work session on Aug. 10 between the BOCC and the Ouray County Planning Commission (OCPC).

Last Monday, OCPC member Ken Lipton came before the BOCC during its informal Call to the Public to read a statement of timelines that included summaries of directives by the BOCC and meetings and work sessions since the process began in May 2008.

“The question as to whether or not a new section to the code should be written was already decided by the BOCC and earlier agreed to by the PC and this should not be negated by self-interested parties or ideology or fear of angering a portion of the community that holds unrealistic views on property rights or the county’s right to regulate land use,” said Lipton from a portion of his document.

According to a news report in the July 31 Plaindealer, nearly 200 citizens packed the county courthouse two days earlier to register their views on the issue of restrictions and regulations for residential development on mining claims. Opinions were as diverse as the backgrounds of those in attendance; some owned property in the area currently defined as the South Alpine Zone, some did not.

Commissioner Keith Meinert said at Monday’s meeting that a news report in last week’s Plaindealer needed clarification. County Attorney Mary Deganhart did not write or propose regulations for that zone. “We need to be careful in the way this is portrayed to the public,” said Meinert. “I want to dispel completely (any belief) that such work is driven by any individual on the staff. The county attorney is working at the instruction of the board.”

Meinert said he agreed with Lipton that there needs to be a better understanding between the BOCC and the Planning Commission.

BOCC Chairman Heidi Albritton said the county’s six-month moratorium on mining claims development was intended to allow time for discussion and consideration of specific regulations; but the timetable was not realistic. “We have a large demographic interested in the issue,” said Albritton. “If there are ways to work with them, we need to do that and get a consensus, understanding that we are not going to please everyone.”

Ridgway area resident Craig Fetterolf, who served on the county’s Study Group that earlier this year completed its report on two separate analysis on the affects of growth, asked why mining claims are not taxed the same as other buildable residential properties. “It’s unfair to the rest of us who are paying our taxes,” he said.

Meinert said mining claims are being assessed at the proper rate of 29%; there is no special treatment by the Assessor’s Office. Commissioner Lynn Padgett explained that the difference is the land’s valuation. Padgett said the state requires the county to assess all property at market value, but there is simply not enough data on local sales.

Padgett added that while a higher assessment of market value may add to property tax revenues, it may also harm opportunities for the public, such as the Red Mountain Project or the Trust for Public Land, to obtain mining claims. A higher valuation will mean a higher price.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)